So I drove back down to Albuquerque and began my winter dormancy. I rode the mountain bike a couple of times a week, played some pickup basketball games when my friends could sneak me into the UNM gym, and rolled around with friends on rollerblades at night. I needed things to do that didn't cost money because I was nearly broke. I had been desperately impoverished the whole year because while I was in my first year on the Shaklee team, I wasn't being paid anything. They gave me a bike (no racing tires though), and paid to get me to and in races. Fortunately, I spent a lot of time on Federation trips that year and was able to live cost-free for much of the season. When I was stateside though, I had to depend on the charity of friends and survive on prize money. That I had a place to live by year end was purely by the good graces of Paul Sery, who had just bought a house in the Nob Hill neighborhood in Albuquerque. My rent was a paltry $110 a month, and I could barely afford it. Further, Paul gave me several months leniency until the next March when I would receive my first stipend check from the Shaklee Team for the '90 season.

It was a big surprise when I got a call from a Federation coach who wanted to know if I could fill a spot on the team going to the Vuelta a Costa Rica. The race start was only a week and a half away. Typically for these international trips the rider was expected to pay their own domestic airfare to the departure point, in this case, New Orleans. I wanted to go but there was no way I could afford the ticket to New Orleans. The coach told me to hang on, and he would see what he could do. Meanwhile I called around to check airfare prices. The cheapest was United at around $500.

The next day he called back and said they could cover my airfare, but they couldn't get me the money until I got to New Orleans. They asked me to drive to Colorado Springs and start the flight from there. Since flying from Albuquerque involved a plane change in Denver, this brought the cost down a bit. I hit my friends up for a loan, and Gabe Aragon fronted the cash, with me having to promise a Colombian jersey as an interest payment. I called the coach back and told him it was on. I asked who else was going.

|

| Gabe "Cabbage" Aragon. A good egg if ever there was one. |

The one other member of Athletes in Action here was Paul Peterson, who I knew as a good regional racer from Minnesota, a good sprinter. From Southern California we had Steve Klasna and Luis Torres, both solid guys. The most notable name to me, though, was Peter Ilovski (not sure if I'm spelling that right). A (I think) Czech immigrant who raced primarily on the East Coast. I had never met him before, but I knew he was nicknamed Peter "In-love-ski" as he was a legendary ladies man. He would live up to that reputation by wasting no time charming a woman who worked at the hotel in San Jose. He even stayed an additional week in the country after the race to spend time down on the Pacific coast with her. I was glad to hear that Robert Gregario would be our race mechanic as he was for us in Guatemala.

Before I left, I had to get a bike together since my Shaklee team issue Cyclops had cracked in Guatemala. Fortunately, I had my old Paterek frame that I had last used in the Ronde Van Belgie in '87. It always felt good to get back on that bike.

The race hotel in San Jose was a nice one, and it was very nice that we would be staying there on each return to San Jose. We had two days before the first stage so we got in a few rides and did a stint in front of the TV cameras as pre-race hype. I tried speaking my piece in Spanish, but didn't do so well. I think they edited it out. The night before the first stage, we were all crammed in Robert's room which was filled up with bikes, bags, and tools. One of the Italian team's riders stormed up to the door and said loudly, "Oakleys! For me!". We all stopped whatever we were doing or saying and tried not to bust out laughing. Granted he didn't know English well and couldn't know that he sounded like he was demanding we immediately surrender our Oakley eyewear to him, but it was super funny. I do believe Steve Klasna eventually did sell his to the Italian at an exorbitant price.

We also talked about how we should approach the race. None of us were in sparkling form; it was December after all. Having been the person who most likely last raced; and certainly last raced in a similar venue, I offered that none of us were going to be able to climb with "these guys". We should ride within ourselves on the climbs, and save our energy for opportunities that might arise on stages that weren't so mountainous. Otherwise, the goal was to ride into the race and hopefully finish strong. I also opined that we should look out for one another, help each other through it if we happened upon each other in the scattered bunch across the mountains. This was sound advice, especially since of the six of us, three were on their first significant international race, and this was a pretty rough one. Indeed, Paul and Dave missed the time cut in the first week. Throughout the race I most often saw Steve Klasna, and Luis gained form later on and was more active late in the second week. Peter came in with the best form actually, but as such, was making maybe the third or fourth split in the mountains. He was our GC leader but not in a position worth defending. His form deteriorated in the second week, and I think that was likely frustrating for him.

The first stage of the race was from San Jose over the ominously named Passeo de la Muerte to Limon on the Caribbean coast. The pass was the only climb on the route but it was a big one; 25 km at a steady 6%. It was fortunate that several factors kept the good climbers from really lighting it up, but for me personally, a puncture about halfway up put me into trouble in short order. Robert gave me a great wheel change and a healthy shove forward, and I even caught back on. Alas, it only took a slight acceleration at the front to pitch me off the back. My residual form wasn't enough.

When I got the call to come to this race I had already been a bit under a month in remission. It was too late to do any real training as such for it. I had no illusions of going for the General Classification; I only hoped to ride into enough form to go for a stage win. So it was that I was more than happy to be in the lead group half way up this huge climb. I came to top of the pass on my own, and it started raining. I did a good descent, and caught up to a decent size group that had gotten sawn off somewhere up the climb.

It wasn't until after I'd stopped that I realized how tired I was. I rolled to a stop, got off my bike and sitting down, rested my back against a palm tree. I knew people would crowd around me and give that feeling of claustrophobia, where the air seems more dense and more difficult to breathe. But I was well practiced from Guatemala twice now, and I knew what to expect. Some children were saying something to me, and not listening, I automatically spat back at them with a tired voice, "No habla Espanol". But then I clearly heard one of them say, though heavily accented, "No! Listen". They were speaking English. It turned out that on the Caribbean Coast of Costa Rica, like in Belize, English is their first language. Not that this made this encounter any better. They wanted me to give them something, like a water bottle. I just assumed they would steal them off my bike like so often happened in Guatemala.

We had a few stages based around Limon before turning back towards San Jose. I suffered greatly on the early stages, but I worked with the groups I was in and was indeed coming around. It was on stage six, a 126km loop starting in San Jose with the finish in a suburb, Santa Ana, that I felt a little like I could try something. I didn't think anything would come of it, but I could try.

It was hot and humid at the start, and at the start line I was lined up mid pack, when I hear Davide Bramati (yes, that Davide Bramati), talking loudly and aggressively at a Costa Rican rider I knew from my two previous Vueltas a Guatemala, Luis Hidalgo. Just as I wondered what the hell was happening, Bramati walked past me to Hidalgo. Bramati was stabbing his finger into Hidalgos chest and shouting at him in Italian. Hidalgo looked kind of stunned and didn't do anything. Bramati walked back over to his bike. I was looking over at Bramati when I see him cast his glance back at Hidalgo, give an expression of surprise and anger, and run back at Hidalgo. Now, Bramati is a big man with some big muscles. Hidalgo is a slight man, a hundred and maybe ten pounds with his clothes on. Bramati lifted Hildalgo off his bike and started wailing on him, landing a bunch of punches.

I was shocked. I was just thinking maybe I should do something when the Bideca (Hidalgo's team) mechanic came running and jumped up on Bramati's back, landing several punches to Bramatti's head. Bramati let off on Hidalgo, and was trying to get the mechanic off his back when several people ran in to break it up. They managed to calm Bramati down a bit and lead him back to his bike and teammates.

After a few tense minutes the Chief Commissar walked up, looked at Bramati, stuck out his thumb and cast his arm back over his shoulder, indicating Bramati was being thrown out of the race. Bramati gave an incredulous look of disbelief, as if to say, "What did I do?". There was then a lot of arguing, Bramati loudly and combatively, the Italian manager more reservedly. The Commissar stuck to his guns though, and Bramati had to leave. The arguing continued, the Italians were insisting Hidalgo be thrown out as well, but that wasn't going anywhere. Their only consolation was the Bideca mechanic got thrown off the tour. Later, Brammati would say that Hidalgo had insulted him gravely by making some crude gesture and making some rude remark concerning Brammati's mother, but that argument didn't help his case at all.

At last we got rolling and a few miles in while the bunch was still rolling along with no urgency, I found myself alongside Hidalgo. I tried asking what hell that was all about, but my espanol wasn't good enough to really get the details. In the end he didn't want to talk about it. Then one of the Italians rode up on my left and starts shouting at Hidalgo over the top of me (another big guy). I didn't pick up what he was saying except I did hear "I'll kill you!". I looked at him and said in English, "Dude, calm down." He glared at me and rode up field.

There were maybe 40km of flat to rolling roads before a huge climb up the mountain to the south of San Jose. There had been a few attacks that had been brought back, so after one of them, I attacked very sharply and got a clean break with one rider on my wheel, Carlos Palacios. Carlos was in the newspaper a lot because he was notably not a climber, but was on a mission to get the highest G.C. placement possible. He wasn't doing too badly in that respect, he was in the top ten. I had nothing to lose, so I pulled all out with him all the way to the base of the climb where he promptly dropped me. I got maybe 5 or so km and to the first premio de la montana, which was maybe a third of the way up the climb, before the field caught me. The leaders were all on the big ring absolutely flying. They were all Costa Ricans and Columbians except for one Ecuadorian and the one real climber the Italians brought with them, Oscar Pellicioti, who looked like he was already on the rivet. Quite a few riders went through me before I settled into a group going at a pace I could deal with.

Steve Klasna was in this group and we just rolled it in to the finish. Once we got back into the lowlands a lot of guys just wanted to sit in and eventually it would just be Klasna and I pulling. I would then sit up and say, in English, with an English accent because I like joking around even if they didn't get the joke, "C'mon lads, let's just make this a nice roll round eh?" It would get a few to come through for a little while before they would fade back leaving Steve and me to haul the laughing group in.

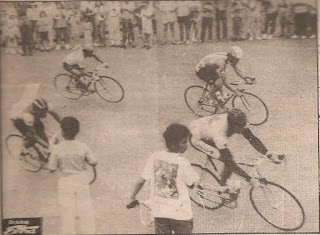

|

| I lead in the laughing group with about 10km to go. You can see Klasna poking his head up 5 guys back. |

The pros have the autobus, we amateurs had the laughing group. The difference is in the autobus, the guys help each other out because they know they have to make the time cut and they also just want to get the day done. In a laughing group, so-called because no one is laughing, most of the guys are despondent, because, well, maybe dreams have been shattered, ambitions dashed, and beatings administered. So they just want to hide in the group and be carried to the finish. Fine. Steve and I would bring them in.

Stages seven and eight were two circuit races in San Jose separated by a rest day. The first circuit, The Circuit La Paz, was 15 laps of a 7.3 km noodle course south of downtown. Basically it was an up and back on a big boulevard with two traffic circles at either end for turnarounds and several traffic circles mid course. The whole thing was rolling big ring hills, with nary a flat spot.

I made the break simply by being on the front pulling. I was just rolling along when I hear a bunch of guys urgently yelling "Vamos! Vamos!". I looked back and, remarkably, we had a gap and the field was spread across the road. It was a big group, somewhere between 15 and 20 riders, so I just kept pulling smoothly and took a few turns out to save energy. The top two Novatos (Young rider) riders were in the group eyeing each other. About mid-race the leader of the Novatos classification crashed, having hit a dog. The teammates of the 2nd place rider went to the front and drilled it. I took this opportunity to sit in and rest.

|

| A distant shot of the break at Circuito La Paz. |

There were two Italians in the group, Davide Perona and Dario Nicotelli. As we hit two laps to go, I made sure I was within reach of Perona, who surely would have Nicotelli lead him out. In the last lap I hitched on to Perona's wheel, with the Cuban rider Conrado Cabrera trying to pry me off. I was pretty good at sticking a wheel, and Cabrera wasted a lot of energy trying to supplant me. This was good, because I knew Cabrera was a better sprinter than me, all things equal. Nicotelli wound up the lead out, slightly downhill leading into a slightly uphill final 200 meters. I knew that if I had any chance of winning, I needed to get the jump on Perona, but I was also hesitant because I knew if I went too early in an uphill sprint, I would lose out. I was correct on both counts: Perona started the sprint first and I reacted fast, first trying to come around at 150 meters. At the line I threw my bike just before Perona threw his and I came up half a wheel short, with Cabrera a bike length off in third. Perona was simply much faster than me, but if I had jumped at 200 meters where he did, I could not have held it. Jumping at 150 meters I came close...maybe if I had jumped at 160 meters...probably not.

|

| Second to Davide Perona at the La Paz Circuit. It looks close, but he had me all the way. |

After we had rolled to a stop, Perona got off his bike and walked up to me smiling with his hand out saying something in Italian which I took to be "Good sprint" with an intonation of "I can't believe you were that close". I shook his hand and said "Grazie!, I have to try right?" I was pleased with the result and truly I could not believe that indeed I was that close. It gave me confidence that I was coming around and that I really could play for a stage win. The first step towards that was getting back to the hotel to rest up. Immediately in the way of that were hordes of kids looking for autographs. Being second in the stage, and not wanting to make us Gringos look like ungrateful bastards, I did the right thing and stayed to sign the notebooks and little scraps of paper.

The morning of the race we rolled from the hotel on nearly car free streets. It was Sunday and the crowds would gather mostly later in the race. I spotted a pink clip-on bow tie in the gutter. I stopped, picked it up, and put it on. "We are going to be on embassy row after all", I said to my teammates. Not only was the circuit in the neighborhood of many embassies, the Presidential estate was on the course. The stage was dedicated to the Costa Rican President, Dr. Oscar Arias Sanchez, a Nobel Peace Prize winner. It was said that he would be there, and would present the trophy to the winner. I saw him at the start, walking through the field with his security detail, shaking hands with the top Costa Rican riders. That was pretty cool.

|

| Mid stage in the high speed corner at the bottom of the course. That's me upper right. Bottom, Canadians Chris Koberstein and David Spears. |

The Italians were intent on the Metas Volantes, and I feigned interest in these as part of my plan. I would start the sprint early as if I were going for it, but then slip onto their wheels. My hope was that they would work a little harder than they needed. The final Meta Volante sprint was on lap 13. Both the Italians were going for the points, and I made a stronger fake surge to get them to go even harder. They finished one-two in the sprint with me on their wheels. After they let up, I hit them with everything I had, and moved clear. The Italians had gotten us a four- or five-bike length lead to begin with, because of their sprint. My first look back showed the bunch was in pieces, but there were two small groups hard on the chase about 5 and 10 seconds back. I kept my pace and another look back proved that the two groups were gaining, but very slowly. I had made the right turn to the flat top stretch of the course before someone caught my wheel. I pulled for another 10 seconds and pulled over to assess. Chris Koberstein came through and I grabbed his wheel. I didn't want to go up the road with Koberstein because I knew there would be games and he wasn't a half bad sprinter; better him than David Spears though. There were a few Costa Ricans with us and the second group was still chasing. I jumped again. I was clear again, but tiring. Someone caught my wheel and soon came through. It was Carlos Palacios. I looked back and we had a good 20 meters on one rider making a weak chase. We made the corner to the downhill backstretch, and we were away.

Carlos was kind enough to let me recover before pulling off for me take a pull. At first I pulled all out because I wanted to get as big a gap as quickly as possible. The sooner we got too far for anyone to bridge, the sooner the chase would get discouraged. I was drilling it going back uphill when Robert Gregario came up alongside me on the motorcycle and tells me Carlo's manager wanted to make a deal: If I pulled without reservation, Carlos would let me win the stage.

I looked at Carlos and said, "Yeah? Yo trabajo duro (I made a revving motion with my fist) Yo gano?" Carlos nodded his head in assent. Just a short time later I was taking a strong pull when I remembered the pink bow tie. I reached up and tore it off, and dashed it to the ground. It looked pretty funny when they showed the stage on TV that night, if only because I knew what I was doing. The picture quality wasn't good enough to tell just what I threw to the ground. I was pulling pretty close to as hard as I could but not quite. I had learned long ago to never to completely trust anyone in a bike race. No matter how well you held up your end of the bargain, they will find a reason to justify breaking said bargain. Nonetheless we made good time. Coming into the finish, I made sure to pull to 400 meters and pull off, keeping a firm eye on Carlos. Dutifully he pulled through, but not full on. This made me suspicious. Indeed, he dogged it at 300 meters, and when I jumped hard at 210 meters, he reacted with gusto. I wasn't too worried because I was still accelerating the whole way, and I could see him in my peripheral vision not getting any closer. But still, I was glad I left something in the tank. I got my stage win.

We finished 46 seconds ahead of the rest of the break, led in by David Spears nipping Perona. The field rolled in three or four minutes down. I barely had time to high five Robert and Steve, and put the Lee branded jersey over my skinsuit before they whisked me away to the podium.

|

| The podium ceremony at Circuito La Paz, Arrival, Trophy presentation, and "Euro kisses" applied. |

They announced me as the winner and then plopped a hat on my head and handed me the ridiculous four foot tall trophy. The Euro kisses were administered by the podium girls and then they whisked me off to doping control. In doping control, drinking Coca-Cola to work up a sample, it occurred to me that Dr. Arias Sanchez was not there to present the trophy. I asked about it later and it was said he couldn't make it because "an important matter of state" had come up. Whether there really was an important matter of state, or if he was disappointed a Yankee had won, I was in turn a bit disappointed. It's not everyday you get to meet a Nobel Peace Prize winner. I don't have the trophy anymore, but I do have the plaque:

|

| The trophy was gaudy, the plaque on it was worth saving. |

This was among my favorite wins. It was one of the very few races where I thought to myself, "I'm going to win this", and then did. I crafted my plan on the fly and executed it. I was especially happy that I had correctly identified that there wouldn't be enough willing workers to chase Carlos and me down. With about 4 laps to go, there were only ten of the eighteen riders in the break pulling regularly. Another two or three contributed occasionally, the rest were just sitting on. I knew then that the numbers of people willing to work would deteriorate as the laps wore on. When the opportunity to attack came, which played out in the Metas Volantes with two laps to go, I counted on the bunch being stretched out, making it more difficult to organize a chase, and once they regrouped, that there would be only five or six guys willing to pull. After pulling around ten guys sitting on, their enthusiasm for this would die, and our gap would increase. This is exactly what happened. I felt like I had cleverly sucker punched the Italians who weren't just any Italians, but guys who were getting serious looks from pro teams. I also felt like I'd gotten back at Koberstein and Spears, even if they didn't realize it. Especially since Spears won the field sprint over Perona, and, status quo, very well might have won had we all rolled to the line together.

The next day it was back to business, however, a sobering 156km from a suburb of San Jose to Sarapiqui via Cuidad Quesada, over a monstrous mountain pass on the west shoulder of the Poas Volcano.

|

| The Google Earth view of the gnarly climb on the west side of Poas Volcan National Park. It is a beefy one. |

I got dropped right on cue when the climbing started, and after over an hour of climbing, went over the top with another Costa Rican I was familiar with, because he had been at the Vuelta a Guatemala, Miguel Badilla. Immediately starting the descent, there was heavy fog limiting vision to about 10 or 20 meters. Miguel was blasting the turns though, and I reasoned that he must know the road well, so I'd better hang on. The road was getting damp from the fog and Miguel kept sweeping the turns, faster and faster. Eventually I had a scary skid in one switchback, and followed that with nearly going off the road on the next. That was enough to make me back off. I had nothing to play for in this stage. I would just take it easy and wait for whatever group came up from behind.

Four or five switchbacks later I saw Miguel Badilla climbing back up to the road from over the edge, his jersey dirty, and a big weed sticking up out of his hairnet helmet. It was pretty comical actually. He didn't have his bike with him which momentarily worried me, but I didn't see it in the road and continued on. Shortly after that, the fog began lifting and I could begin descending with more confidence. I swept through Cuidad Quesada and after turning East towards the finish, picked up a small Colombian rider, who had been dropped and left for dead by the field. He immediately jumped my wheel, and began telling me his story, in rapid fire Spanish.

It should be clear by now that my Espanol was in that terrible place where I could understand enough to know what was going on, but not able to garner details or speak back without sounding like an idiot. Nevertheless, I was able to pick up that he 'knew the Costa Ricans were 'doped to the gills' and '(the Colombians) couldn't do anything because they were tested every day'. He apologized several times for not being able to pull, because he was completely destroyed from chasing on the climb. I told him it was ok. It was about 90km from Cuidad Quesada to the finish, and I was plugging along at a decent clip. The terrain was heavily rolling, with the occasional sustained climb where the Colombian asked me to slow down (I'd never had that happen before...or again).

I was surprised that we hadn't come up on another group, or that one hadn't picked us up. We had been together for an hour or so and the Colombian had been talking at me for almost all of that time. Then a car came up, and the driver pointed up the road, and said, "40 kilometers, puro plano a la meta". This I understood, and it was quite cheering. Soon, if what he said was correct, we would have 40 km of "purely" flat roads to the finish. The Colombian looked relieved.

It wasn't quite that way though. The rollers got bigger, and there were a lot of false flat uphill drags. I was getting tired, and this terrain seemed never-ending. We had been at this for twenty or maybe thirty minutes when Senor "Puro Plano" came up again. The Colombian was quite cross at him. "Donde" he demanded, 'is the 40 km of "Puro Plano"?' Again the driver pointed up the road, and drove off. We went another 10km or so in sharply up and down terrain, and were flying down a steep descent, through a sharp turn when before us we see, straight and covering a good portion of our field of vision, an absolute wall of a road. I sat up, turned and looked at the Columbian. He too was sitting up and looking disbelieving of what he was seeing. I stuck out my arms and circled my wrists back up and double 'flipped off' the 'wall' (Just like Otto in "Repo Man" when he quits the grocery store).

The Colombian thought that was pretty funny and he did it too. But we still had to climb up the damn thing. After 10-minutes of struggling, a clear plateau opened up before us, and finally we had our 40km of puro plano. The Colombian's mood significantly improved and so did mine. But then I thought, 'man, there's still 40km to go!' I was down to the wee ring now, going maybe twenty, twenty-three miles an hour. It was all I could do. About half way home the Colombian began contributing a bit, but he was slower (which told me that he was truly cracked). Eventually we saw a 5km to go sign, a 3km to go sign, and then, with the 1km sign just in sight the Colombian lets out a yell of rage. I look back and see a 25 or so rider group, led by none other than the soiled Miguel Badilla rapidly closing on us.

That we could have, say, just sat at the roadside and waited, we could have rolled in relative comfort in this large group. Or, if the group had just been faster, maybe they could have picked us up sooner, But no, they had to catch us just when it wouldn't be any particular comfort or help. I thought it was kind of funny, but the Colombian was despondent, I'm not sure on my behalf, or his, or both, but in any case, he pulled off to the side and let the group pass, without tagging on. Surprised, I did the same in solidarity; whatever that solidarity was. It didn't matter. I'd slogged for two and half to three hours with this guy. I was crossing the line with him, and him alone.

That night we stayed at an Eco-lodge, La Casa Verde, in the depths of a rain forest. In the open-air hallway to our rooms, there was the biggest spider I had ever seen clinging to the wall. Being quite the arachnophobe, I stepped very carefully around that spot, and really had trouble sleeping that night, even though the room was nice, tidy, and clean.

The next stage started in Cuidad Quesada, immediately going up the descent of the same monster climb we had done the day before and then descending down to the Pacific coast to Puntarenas. On the bus trip over, a Costa Rican rider was lining up pills on the seat. He saw me looking at him, and he says, "No es las droogas, es azucar". Whatever, they probably were, but I could see the outlines of the syringes in his jersey pocket. One thing that had been obvious to me throughout the race, was that these guys were high on amphetamines when it was time to climb. They were doing steep 20km climbs on the big ring, completely inhuman. That the Italian Pelliciolli was 9th overall a mere five and half minutes down and that he was generally able to stay with them to this point was truly incredible, as it wasn't apparent to me he was "on" anything. Costa Ricans occupied the top 6 spots on GC, Raul Montero leading, followed by his teammate Alfredo Zamora at 3 minutes, Luis Morera of Bideca, Carlos Bermudez, Andreas Brenes, and Mario Fallas at about 4 minutes back. The rest of the top ten was occupied by foreigners, Hector Palacios from Colombia, the Ecuadorian Juan Rosero, Pelliciolli, and finally another Colombian of some note, Ruben Marin.

We had gotten to Cuidad Quesada pretty early and I was tired. I wasn't in the mood to warm up, because it didn't matter anyway. I was going to get dropped straight away. and there would be thirty minutes of people going as hard as they could until they settled down and we could get a group together and roll to the finish. It was fairly pleasant out though with the warming sun on a slightly chilly morning. I went to the start line absurdly early and waited soaking in the sun. Eventually the GC contenders and their domestiques started coming to the line. They were intense, focused, and their arms were shaking, some had facial tics. They all looked older than they were, and this made me strangely sad. The start was on a 6% grade and their bikes were all shifted to the big bracket. I was soon surrounded by them and it was clear I didn't belong there. I got off my bike, and in English said, "I'm going to just get out of you guys' way", and in parting "Buena suerte".

Watching the TV coverage that night in Punterenas was unbelievable. They were sailing up the climb like it was flat ground, rotating, even. They were all in the big ring the whole way, and at the back of the lead group were the Colombians, the Italian, and the Ecuadorian. Pelliciolli looked particularly stressed, but he hung on.

There followed a few stages on the Pacific side of the country. One was a flattish stage that I thought perhaps I had a shot at. My hopes dimmed considerably however when four of the five remaining Italians made the break. The break also contained the Novatos leader with two of his teammates, and a few other Costa Ricans. I couldn't sit on because I knew they wouldn't let me. The field wasn't too far behind so some team or teams were chasing, if they wore themselves out a bit, so much the better for later if they ran us down. So I pulled softly at the opposite end of the rotation from the Italians, who were determined to keep the speed up.

Then, shockingly, the Novatos leader crashed, having hit a dog, just like the previous owner of the jersey. Next in line for the Novatos was a young Italian. The Italians really hit the gas. Due to the acceleration I moved up to the Italian's wheels and I had a look back, the Costa Ricans were all going to sit on, even the ones that weren't teammates of the Novatos leader (apparently this young man was quite popular). Nicolleti began pleading with me to work, but I decided to refuse, "Lo siento, no" I told him. I immediately came up with several reasons to not contribute. First, the Costa Ricans would hold me in higher regard for acting this way, and I thought it more likely that I would see them before I would see the Italians again. I could bank some good regional karma. Further, and even more significantly, if I did help the Italians and we held the field off, there were five Costa Ricans sitting on that would overhaul us in the end. If even I were to assume the Costa Ricans weren't a threat, I still had four Italians to contend with. I don't think if even I had helped them, a deal would have been forthcoming.

The Italians pleaded with me several more times to help. I kept telling them "Sorry, but no". They finally gave up, and the field caught us back about 7 minutes later, the team of the bloodied and battered Novatos leader on the front.

The second to last stage was basically a long dragging climb that got progressively steeper to the finish, where the highway from Puntarenas to San Jose crested. I had been feeling better and better on the climbs in the second week, and found myself in the lead group surprisingly far into the stage. When the last pitch began, and the GC leaders started attacking, I went straight out the back as usual, but this time I started picking off the people and groups that had gone too hard and cracked, and halfway up, I could still even see the lead group only three or so minutes up the mountain. I could see them by virtue of their going slower...not so much me going faster, but in any case, that didn't last too long. They soon pulled the gap between us to seven or eight minutes, the closest I was to the leaders in any mountain stage here. A short while later, I picked up another rider, but this time it was Pellicioti, the Italian GC leader; he had finally cracked. I looked over at him. He was straining at the bars and sweating. "Vamos" I said, slowing a bit and letting him catch my wheel. He stayed with my pacing and recovered a bit. Then the Italian DS came up in a car and started yelling at him. Pellicioti just hung his head a stared up the road. I felt really sorry for him, and eventually he fell off even my wheel. I briefly considered waiting for him, but I wanted to get the stage over with and continued on.

As if the stage wasn't hard enough, the accommodations that night were terrible. Cinder block cells with rickety cots and primitive toilets. I don't remember what the shower arrangements were, but I don't recall them being very comforting. Earlier in the year I had been in Italy at the Giro della Regioni, and they put us up at some real dives, but this was really bad. All of the Costa Rican teams drove to San Jose and either stayed at home or a friend's place. All of us foreigners had little choice but to stay. We had a terrible meal, and a cold restive night's sleep in what seemed like a prison camp.

Remarkably, At breakfast the next morning, I felt like I'd had worse nights of sleep before. I woke up feeling quite all right, glad there was only one stage left. It was a rolling, gradually uphill affair to San Jose. It should have been a nice roll 'round to the finish, but there was the stage win to play for, and maybe even a few scores on GC to settle. It was all out war, and the field shattered. I wound up riding with Steve Klasna and Luis Torres, with a few others tagged on. We rode within ourselves and just dragged our tired bodies to the finish, many minutes down on the winner. It was finally done, and I was glad it was over. We were about to ride off to the hotel when Robert came up and told me they were calling me to the presentation stage. I couldn't imagine why. I went up and they again announced me as the winner of the Circuito Presidente, and handed me, courtesy of the Italian Embassy, a gargantuan 7'1" tall trophy. I held it up facing the crowd (with the help of the presenter), raised my other arm and all that, and exited the stage, carrying the trophy with both hands. I set it down to the right of the bottom of the steps and wondered, "How the hell am I going to get this home?" meaning on the plane ride back to the United States. Robert was right there and he took it over to our support truck to haul it to the hotel.

It was a job packing everything up, as I had to dissemble the two trophies. To keep the pieces straight, I stuffed one in my bike box, and the other in my duffel bag. We were up early the next morning for the airport, but could have slept in. It was hurricane season back in New Orleans and so our flight back was delayed several hours. We spent the time hanging around waiting outside the terminal with the Canadians. There was some drama around one of the Canadians having skipped out on a telephone bill at the hotel, but nothing came of that immediately. I imagine the Canadian Cycling Federation was none too pleased, eventually.

|

| Waiting outside the San Jose terminal. From left Luis Torres, the coach, me and my stylin' Adidas. No Canadians in sight as yet. |

Our plane was finally cleared to take off and we knew we would be spending the night in the New Orleans airport. However, that wasn't the only trauma remaining. It was very foggy on the approach to New Orleans, and as I was watching through the window, breaking through the fog I saw that we were close to touch down, and we weren't centered on the runway. It looked as if the left wheels would land off tarmac. The plane banked hard right and left again and the plane set down hard on the runway. The oxygen masks all popped out their compartments with the impact. It was, I suppose, a nifty bit of flying.

|

| We took the spot behind the Chrysler display, the Canucks were up off on the left side. |

We camped out by a Chrysler display and had yet another terrible night's sleep. Eventually I make it back to Colorado Springs, checked in at the coach's office and gave Jiri my story while I unpacked my bike. He asked if the office could have my 7-foot tall trophy and I gladly gave it over. It sat in their trophy room for a while, and eventually disappeared. I heard some rumors about where it ended up, but I can't substantiate any of them.

I drove back down to Albuquerque in my thoroughly rusted Mazda 808, resumed my winter dormancy for another couple of weeks, and then resumed training for the next season. It would come sooner than I expected.