I had alluded to my poverty-stricken year of '89 before in my Costa Rica posting; but of course that was the end of '89. The year started rather more dramatically. Even though I hadn't gotten to go on a federation trip in '88 (I did the Vuelta a Guatemala with my Paramount CC team though), the federation coaches still had their eye on me. I was invited to the 'Team USA' training camps in Colorado Springs at the Olympic Training Center. I was also invited to the more exclusive national team training camp at Wonder Valley in the Sierra foothills east of Fresno CA following the Colorado Springs camps.

I drove my father's '72 Ford van (resuscitated for the fourth or fifth time now) to Colorado Springs from the farm in western Wisconsin. The 'Team USA" camp at the Olympic Training Center run from early January to February 3rd, was an exercise in brutality. Team USA was a new concept that year. The idea was to have a team of riders that would make the bigger part of the key national team trips so that they weren't at the mercy of trade team managers allowing their riders to come on those trips. As it would turn out, they were still pretty much at the mercy of the team managers.

The daily plan was exhausting. We woke at 6:00 and by 6:30 were outside for some light exercise (some sort of calisthenics or jogging) before going to the gym for some stretching. Then it was an hour for breakfast, followed by the day's ride, generally 2-5 hours. This was followed by a quick lunch and a little free time. We then had to report to the gym for some weight lifting, some ball court type game (volleyball usually), and some additional yoga type exercise. The total time of the 'gym' work depended on how long the ride was. Of course we all best liked the days with the longer rides. We then had another hour of free time. Around 4 or 5 pm we then took a bus up to a pool where we either played water polo or swam laps. Then it was back to the OTC for dinner and bed. We followed that schedule every day.

It may seem like it would have been fun, but day after day it was quite difficult. Only one person completed every workout and that was Chris Petty. I missed four workouts; one to a dental appointment (a big bonus of going to the OTC was free medical), the others to shin splints that forced me to miss some of the morning jogging routines. People were dropping like flies due mostly to overuse injuries and sheer exhaustion. Some people skipped workouts they didn't like because they were disgusted to learn that although ostensibly everyone was there for a chance to make Team USA, the team was already obviously picked. We knew this because they were already installed as permanent residents at the OTC, and they could skip workouts as they saw fit without penalty. Personally, I found it kind of funny. At one point Jiri told me he would like to get me on Team USA but couldn't swing it. I wasn't so sure I wanted that anyway. The set up was pretty sweet, but there were a lot of obligations that limited your freedom. I didn't fancy being under the microscope like they most certainly were. As it was, only one person got into Team USA via camp attendance, and that was, of course, Chris Petty.

After surviving the camp, I drove to Albuquerque to train for a week before continuing to Fresno. I reckoned on leaving Albuquerque late, driving through the night, napping a bit early morning in Bakersfield, and then completing the drive to Fresno. It wouldn't go as planned. It was about midnight and roughly 30 minutes outside of Flagstaff when the van suddenly shut down. Engine, electric, everything. The van was just free coasting in total darkness when just as suddenly everything snapped back on. Though quite spooked, I continued.

It happened again at Yucca AZ, about halfway between Kingman and Needles around two or three AM. This time it didn't snap back on. I steered the van to the shoulder and slumped over the steering wheel. I was wondering what in hell I was going to do now. I had very little money, and I was sure fixing whatever the problem was wasn't going to happen either quickly or cheaply. As I was pondering this I heard a peculiar noise like a 'vip...vip...vip'. I opened the door and jumped down to the pavement. A look under the steering column revealed two wires hanging down joined in a plug that was glowing orange dripping flames of burning plastic onto the floor mat which was now catching fire. I threw the mat out onto the road but the fire had already caught on to all the plastic in the steering column. I had only moments to think because the fire was now spreading fast under the dash and onto the engine cover. It occurred to me to disconnect the battery, but the toolbox was buried in the back and there wasn't enough time. Besides, I didn't have an extinguisher or enough water to quash the fire even if I stopped the electrical fire that was feeding it. I got everything I could out of the van before it was just too dangerous. I got out my bike (and the mountain bike I was ferrying for Chuck Veylupec), my 'civilian clothes' and a few other things. I lost all my cycling clothes including my shoes and helmet. My tools, pump, some tires...all burned in the inferno that was my dad's old '72 Ford van.

It was an amazing thing to watch. I was a good distance from the van already but the heat pushed me back farther. The tires exploded, the windows blew out, and I was afraid the gas tank was going to explode. Fortunately I had previously lost the gas cap and just had a rag stuffed in there. When the gas caught fire a flame shot out the side like a flamethrower. Thick black smoke was blowing across I-40 and I was amazed at the semi trucks hammering through the smoke like nothing was happening. The fire raged for about 20 minutes before it finally started to die down. Now there was just the frame of a burning hulk. The magnitude of all this was just beginning to sink in when I heard a voice calling.

A trucker had stopped on the far side of the van, and was checking to see if I was ok. This guy is yet another person to whom I am eternally grateful. He was still with me when a another guy came by (after the fire had pretty much died down). He pulled up alongside with a flatbed truck, casually got out, jumped up on the flatbed where there was a water tank and pump. He had to hand pull start the engine for the pump and it took some time for the pressure to build up. He sprayed until the fire was out, shut off the pump engine, got back in the truck and drove off. Not a word to either the trucker or me.

Shortly after, an Arizona State Patrol officer arrived and asked me what had happened. I ran down the story. He had other questions for me including what I was going to do. Among other things I told him I was very short on cash, and he asked the trucker if he had room to take me to Bakersfield where I could take a bus to Fresno. Apparently, this type of thing was strictly speaking illegal, but the officer took pity on me. Luckily for me, the trucker had only a half load and was willing to help me. The guy who put the fire out then came back with a tow truck and hauled the burnt out wreck away. "Don't worry", the officer told me, "We won't charge you for this".

The trucker dropped me off at the Greyhound station in Bakersfield after buying me breakfast at a diner. I spent a good chunk of the cash I had left on a bus ticket (and extra baggage fees for the two bikes) to Fresno. I managed to get hold of Jiri Mainus by phone and explained my situation.

The bus trip was without incident and I sat for an hour waiting in Fresno to be picked up. I recall feeling the weight of my troubles melt away when the federation car pulled up. It was nice to know that for now, I would have few worries. The federation would take care of me for the next several weeks of training and racing in the Sierra Foothills . Fellow riders lent me jerseys and shorts. The federation lent me shoes and a helmet. They also had to lend me pedals since I was not yet on clipless pedals, and that's all they had for shoe compatibility.

In contrast to the Team USA camps, this was more like it. We woke up, had breakfast, went for a long beautiful ride in glorious weather and then had the rest of the day for ourselves. We alternately went down for flat riding alongside orange groves in the valley, or east up into the hills for climbing. The roads were fantastic and on the weekends we did Bob Liebold road races.

*************

I had spent a nervous winter looking for a team. When a lead to ride on an Avocet sponsored team run by Mark Caldwell fell through, I just managed to nab a non-paying spot on Shaklee. I had acquitted myself well at the camps, and was selected for one of three national teams at the Tour of Texas. After the Fresno camp I stayed with Matt Newberry in Reno before catching a ride down to San Diego to collect some Shaklee team schwag and take in a couple of races with my new team. I then caught a ride back to Albuquerque. After a little over a week of training in Albuquerque, I was off to Texas.

I was pretty anonymous for most of the Tour of Texas until the second to last stage; a big, lumpy wind swept circuit at Bourne. With about 30 miles to go I attacked on a whim up the right gutter on the biggest hill on the course and got a gap. Alexi Grewal bridged across and the gap got bigger. This was a big deal because Grewal was high up on GC and surely the 7-11 team had to react. Eight or so more guys came across, including Steve Larsen, Matt Newbury, and most notably, Alex Steida from 7-11, who of course sat on. I had a lot to gain from this move working so I poured on the coals with my pulls. So it was that when Matt Newbury attacked late in the stage I had nothing to give in response (neither did anyone else) and Matt won the stage. I managed 6th and moved to 13th overall. Incidentally, on the last stage, Alex Steida took the overall win away from Grewal.

That stage sealed the deal for me making the list for the English Milk Race in June, which was exactly what I wanted. The Milk Race, along with the Eastern Bloc Peace Race were the two most prestigious amateur races in the world. Good rides in either of these races could lead to bigger things.

After Texas I got back to Albuquerque absolutely penniless, and as it wasn't yet early April. I was very fortunate that several friends in Albuquerque were extraordinarily generous in being willing to feed and house me in this time. Carol Shermer, Gabe Aragon, Greg Overman and his family. I was at Drew Gagne and Anita Lopez's house when on April 19th I got a call from Jiri Mainus.

I have no idea how he found the number to call me, but nonetheless he explained that Eddie B. was denying the riders Jiri wanted for the Peace Race, and so he needed me to go to the Peace Race instead of the Milk Race. This wasn't really what I wanted to do, but on the other hand the trip also included two weeks in Italy with two one-day races and a stage race. Pretty much a bit more than a month of cost-free living and racing was more appealing than my uncertain race schedule and having to survive on scant prize money. I had managed to scrounge up some cash, from odd jobs people gave me and some prize money, most of which came from a third place at the Tempe Grand Prix where I got worked over by Canadians David Spears and Chris Koberstein (as also described in my Costa Rica post).

Those then, were the circumstances that led me the very next day to O'Haire airport in Chicago to fly to Rome. The rest of the team was made up of the core of Team USA, Chris Petty, Chuck Veylupec, and Steve Larsen. We were fortunate to have James Urbonas along, a race winner who had Eastern Bloc experience. Tommy Matush added sprint power.

Once in Rome we were taken to a small working monastery just at the bottom of a hill to the Southern Rome suburb of Rocca di Papa. The monks were all young, friendly, and liked playing foosball. The rooms were comfortable if spartan, and the food was good. We got our bikes together and did a short spin. The next day we rode down to the coast to Anzio and back. We went up the hill to Rocca di Papa and stopped for coffee in their nice town square. We were then given the choice to race the Trofeo Adolfo Leoni, a 154km one day race with at least one significant climb on the course. That night, I was awakened by a rumbling sound, and my bed was moving, chattering on the floor. It stopped suddenly. Having grown up in Wisconsin, I had no idea what had just happened. "What the hell was that?" I asked my roommate, Chuck Veylupec. Chuck was from around Sacramento, and in deadpan answered with a an admonishing tsk, "that was an earthquake".

|

| The Race bible cover |

We had a solid breakfast in the morning and waited for the cars that would take three of us up to Rieti for the race (I don't remember who else came along). The drive seemed long to me, and our driver took a wrong turn somewhere. We got there in plenty of time though. The start area was a circus. There were throngs of spectators and an awful lot of racers. We were lined up about 50 from the front and there were a hell of a lot of guys behind us. It turned out the field was over 300 guys. Mostly Italians, with a few foreigners like us here for the Giro delle Regioni.

The race began with 5 short laps around Rieti. We then did two laps of a slightly larger circuit which included a passage through a city wall archway on a cobbled street. That led to a much bigger circuit on flattish open territory before hitting a fairly big climb. Then back to Rieti, starting out on the same big circuit that deviated to another bigger climb, cresting about 16km from the finish.

|

| The race profile and past winners |

The first five short circuits were awful, because of course everyone behind was desperate to move up, and everyone up front was desperate to stay there. We would sprint all out, then lock up the brakes. There would be a lot of cussing in Italian until we were sprinting all out again. This went on until we got to the bigger circuit that went through the city wall.

The real action began when we got to the first of the two larger circuits. It was windy and there were splits. I had managed to make it into the second split, and we rejoined the first split on the first climb. I was hiding in the bunch, about 50 riders now, as we left Rieti for the final circuit. It was pretty calm until we hit the climb and it was all out. I was pretty far back in the bunch when it started but I was climbing well at that time, and was able to move up through all the guys who had blown up. Catching the front was out of the question though. I went over the top alone and started the descent. It was steep and none of the switchbacks were consistent with another. I generally had a policy of not taking chances on descents I didn't know (and generally this had served me well), so I took it pretty easy, suffering abusive words from Italians zooming past me because I was in their way. With a little work at the bottom I caught all those guys back and we had a group of a dozen guys or so going for 15th place. I started my sprint way too early and ended up, if I remember right, in 22nd. It was won, remarkably I thought at the time, by Djamoldin Abdujaparov.

This was a fun race and I was stoked to have raced reasonably well so soon off the plane. My previous experience in Belgium was a big help because I was well prepared for the aggressive pack dynamics. From a positioning skills standpoint I found it relatively easy to keep towards the front so I could see what was going on and make reactions.

Two days later we had another one-day race, the Liberatzione in central Rome. This one, it would turn out, was not as fun, for me anyway. The Giro della Liberazione, always held on April 25th, is in celebration of the fall of Benito Mussolini's fascist government in the midst of the German retreat from Italy in 1945. The race was held right smack in the center of Rome starting at the Terme Di Caracalla (the Roman Baths). The course was a series of straights and many u-turns. A key part of it radiated out towards the river alongside old city walls. At one end, we did a U-turn at an opening in the wall and raced back uphill on the other side.

|

| Liberazione race bible cover |

|

| The crazy course. |

There were 400 starters for this one. I was absolutely flabbergasted by the number of guys in front of me at the start line; I was even more astonished by the number behind. The race started fast and (as far as I know) never let up. The whole time was just a mad high speed scramble to move up a place or two here, lose a place or two there. At no point could I see the front of the race. All I was doing was going about as fast as I could, and braking, sprinting, and braking on endless repeat. Just as I was thinking I should quit and save it up for the stage race starting that same evening, I was sprinting out of a U-turn when I look up to see a big Italian guy standing right in my path fiddling with his bike. There was nowhere for me to go. I plowed right into him and landed on the other side of him. I got immediately up, picked up my bike and jumped on, only to discover that my forks had been bent back. Game over. It was also game over for my Schwinn Paramount. Not only were the forks destroyed, there was a bubble in the down tube just behind the head tube. That really bummed me out. That was a nice bike.

The winner, and while someone has to win it still amazes me that amidst all the chaos that surrounded me there was an actual race going on, was Joachim Halupczok from Poland, who would win the amateur world road championship later that year.

The mechanic scrambled to get one of the spare bikes ready for me before we left for Avezzano. I can't remember what bike it was, but the mechanic did a great job of getting things in the right place. I remember feeling quite comfortable on it for the Giro delle Regioni Prologue that same evening.

|

| The race bible cover |

The prologue was in an unusual format. It was on a 900 meter criterium circuit that was done in heats. Each team had one rider in each heat; resulting in six heats in total. The winners of each heat went to the final, and of course the winner of the final took the first race lead. There were no time bonuses for the top places.

I got second in my heat. I was too tentative in the final corner and got dusted in the sprint. Chris Petty however showed no such hesitation, and bombed the corners, scaring all the other guys in his heat to death to win by the length of the finish stretch. In the final, Chris did the same thing and, while by not as big a margin, won cleanly.

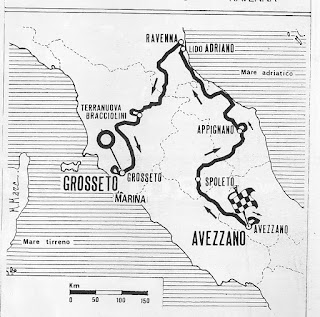

Sponsored by the Italian communist party newspaper l'Unita, the Giro della Regioni was an important race on the world amateur racing calendar. It was a like an amateur version of the Tirreno Adriatico, although this was more a Adriatico Tirreno. Held in the middle of the Italian peninsula, this time starting in Avezzano, racing north to Ravenna, and then southwest down to Grosseto. In general geographical terms: starting in the midst of the Apennine mountains, over to the Adriatic Sea, back across the Apennines to the Tirreno Sea. That it was sponsored in effect by the Italian communist party also meant there were nations in attendance one might not normally expect like Mongolia and China (each which had a rider who was pretty damned good).

|

| The whole thing |

|

| The winners list |

|

| Stage 2 detail |

For me, Stage 2 from Avezzano to Spoleto was 145km of misery. The good form I felt back in Rieti had seemingly abandoned me. On a cold rainy day that wasn't helped by a long gradual descent into a hard lumpy finish, I was startled and ultimately frustrated by the fact that no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn't reach the front. When the racing really started with about 50km to go, I would try to move up on the short punchy climbs and despite a lot of effort, would be discouraged by the number of guys yet in front of me. It seemed genuinely hopeless. As I floundered in this hopelessness, the temperature dropped and the rain got heavier. I felt like I was being dragged by the nose up the climbs and subsequent descents. On the descents we went through unlit tunnels that were completely terrifying. Some were fairly short and straight, but for a few seconds it was completely pitch black and I would begin to feel my sense of balance abandon me. Light would come dimly back into view just in time. A few were longer and curved. For these they lined up motorcycles with their lights on to act as guideposts.

As a result mostly of the tunnels rather than the climbs the bunch shattered. I have no idea where I finished or where my teammates finished. I think I was roughly in the top third of the bunch but I was so cold and dispirited I went straight to the car to find out how to get to the hotel. I went to bed early that night. I probably looked at the results but I don't remember even vaguely what they were.

|

| Stage 3 |

My attention snapped back for Stage 4, a mostly flat 196km from Appignano to Lido Adriano just outside of Ravenna. The rain was back, but it was warmer at least for the start, and there was a strong tailwind for most of the stage. I finally got back into race mode after we turned back inland from alongside the sea. I had just taken off my leg warmers as the rain had let off, and dropped my rain jacket back with the car when the Poles began ramping up the pace in anticipation of the two climbs coming up. They were confident Halupczok could win especially if they could burn out or off other sprinters. It was fast up the first climb where we still had the tailwind, and even faster up the second climb. It was so fast that I felt compelled to climb it in the big ring. I had a look back and saw the bunch was single file pressed on the left side of the road. The climb had some switchbacks and when it turned west there was a strong crosswind. The climb wasn't terribly steep but the pressure was definitely on.

We crested the climb in a crosswind and a few gaps started opening. The descent was gradual, with alternating sections of tail and crosswind. Two things then happened: The temperature dropped from somewhere in the mid 50s to what sure felt to me like the mid to lower 40s, and the rain started hammering down. As mentioned, I had dropped my rain jacket and leg warmers back with the car. With only arm warmers for extra clothing, I froze. Back down on the coast and again with the tailwind, I was safely in the bunch. A few groups got sawed off over the last climb and descent, but the bunch was still pretty large. Halupczok indeed took the win. I was in no shape to contest anything. I was just glad the Poles got us there as quickly as possible.

Chuck Veylupec was my roommate that night. When we got to our spartan room with linoleum tile floors, there was no hot water (as in, the place I think didn't even have a hot water heater). There was also no heating in the room. We took cold showers and put on every dry piece of clothing we had, and got into our beds hoping we could warm up. I managed to warm up in about half an hour, but Chuck was still shivering violently after an hour. I went out looking for hot tea and some food. Thankfully, the hotel office had some hot tea and I got some food from our mechanics. Chuck finally warmed up, but it was still tough for him to get out of bed for dinner.

The next day was the 'queen stage', a mountainous trek back southwestward over the Apennines from sea level Ravenna to Terranuova Bracciolini. The rain thankfully had moved on and it was a pleasant partly sunny day. At 175km this was the day that would make the most difference. I was already well out any chance to get a respectable GC place, but a shot at the stage or at least moving myself up in GC was in play.

|

| Stage 5 time table |

|

| Stage 5 |

Race profiles are often deceiving. In the end the climbing you see in the profile wasn't nearly as bad as it looked. Despite my preparedness, I was too far back on that first sharp bump on the profile, and I missed the first split. We descended back down the other side and the front group was out of sight. The sprinters and other big men in the group were sitting up and calling for "Piano". I wasn't ready to give up. I jumped away from the group to a chorus of whistles and Italian cuss words. The second climb on the profile above looks pretty bad, but it in reality was more like a long, slightly uphill valley. I hammered up the road for 25km and the only person I saw was Steve Larsen who was not interested in pressing on with me. I wasn't sure if he'd been dropped by the lead group, or like me, had been making a desperation bridge. The road then turned gradually downhill for about 5km to give me some respite.

Then the real climb started. It still wasn't a killer, but it was enough to get me in the small ring and pace myself. Now I started seeing the people who had been dropped. That I was going through people just now meant two things: I was reasonably close to the group, but also the group was moving fast enough to drop people. I still had a big and difficult bridge in front of me. I got over the top without having seen the bunch or even the back of the caravan. I was really beginning to think my move was in vain, but pressed on anyway. I wasn't looking forward to being reabsorbed by the bunch I had left behind.

The descent was big, sweeping open turns that I could see through and I was going well. Jiri came by in the car, and Chuck hung his head out and shouted some encouragement at me. His frozen night had been too much for him. I got a couple of bottles and they continued on. Shortly after, I was caught by a trio of Belgians. I was quite surprised to see them. I assume they came from the group behind, or perhaps they had been dropped on the climb and were trying to get back (though I didn't remember seeing them). I jumped on the back of their train. They had caught me as I was getting close to the bottom of the descent, back in the trees, where the turns were getting tighter and harder to see. The Belgians weren't giving the lack of vision any respect and were tearing through the switchbacks at frightening speed. After several switchbacks of going from one edge of the road to the guardrail on the other side, not knowing if my tires would hold, I finally decided it wasn't worth it and backed off, letting the Belgians go. This despite that I was still descending quite fast.

Three turns later (and this the second to last switchback), I saw three bikes lying on the left side of the road and no Belgians. Just as I swept past I saw one of them start to climb back over the guardrail. My 'take it easy on crazy descents I don't know' tenet served me well once more. After a few more kilometers of hard riding, I finally saw the back end of the caravan on a long straight section of road. It was probably a two or so minute gap. The road was gradually downhill to the last climb, but I had been at it now for about 50km and I was tired. My resolve to keep pushing was disappearing and doubts began creeping into my head as to whether I could cross the gap.

Then I had an incredible spot of luck. I saw a team car parked up ahead on the right. As I sped by I saw four riders stopped. The Danish GC leader had punctured or had some other problem and three of his teammates had stopped to pace him back. I eased up and waited for them. I jumped onto the back of their chase, and in short order I was in the front bunch, just as we started the final climb. The group was about 35 to 40 riders strong.

Fortunately for me, the final climb was not at all serious. We went over it in the big ring and it was fast enough that I had a draft to help pull me along. James Urbonas was in the group but I had to confess I was too shattered to be any help. As it was, James didn't particularly need my help and won the group sprint for 4th place. We thought he had won, but we had missed that a small group had slipped away and a Russian won.

|

| Stage 6 |

Stage 6 took us down to the Adriatic sea at Grosseto. The day was a double stage, 122km from Terranuova Braccolini to Grosseto, and a 12 lap circuit race on a 3.3km circuit (only 39.6km) in Grosseto. Nothing happened. The racing was fast but without drama. After the circuit race they herded us all into a cafeteria where we all ate in a big noisy room. I remember being in line behind a Columbian who, when the lady dishing out the fried potatoes put just one little ladle full on his plate, just kept saying rapid fire "Papas, papas, papas..." until she started putting more on the plate.

I finished the Regioni in our team's best GC spot, though in a nothing to write home about 33rd place. We drove back down to Rome, and a day in the city before flying to Warsaw for the Peace Race. We were back at the monastery, and took the train into the city. We looked at some Roman ruins and did some shopping for supplies that we would have trouble finding behind the Iron Curtain. This was 1989, and the Berlin Wall wouldn't fall for a few months yet. I didn't have much money but bought a quarter kilogram block of dark chocolate. Chris Petty did the same. We were walking back down the street to meet back up with the rest of the guys when Chris comes up from behind me, "Ugh, Rich, can you finish this?" He had eaten about three quarters of his block and couldn't get down the rest. I didn't expect that. "Damn man! You ate all that? Just now? Wrap it up and save it for Warsaw."

The next morning we boarded a Polish Lot Airlines jet for Warsaw. In the pre-flight safety instructions, the voice over the speaker said in the course of things, "smoking will be on the right side of the plane, non-smoking on the left" (this was in less enlightened times). The in flight meal was a selection of bland sausages. This was only a small taste of what was ahead of us.

|

| Race bible back cover - The stages |

|

| Race bible front cover |

The Peace Race, as I mentioned before, was one of the two most important races in the amateur race calendar. It had a reputation as an exceptionally tough race. Warsaw-Berlin-Prague; it had a lot of flat ground before reaching some mountains in then Czechoslovakia. In all that flat ground were legendary crosswinds. The major Eastern Bloc (East Germany, Poland, Russia, and Czechloslovakia) teams would combine in an impenetrable rotating mass that tore pelotons apart. Then they would get down to trying to crush one another. It was also said that if you tried to get in that impenetrable rotation, they would crash you out.

It was remarkable, then, that several years earlier Thurlow Rogers finished fourth overall. Details were scant in Velo News back then, and in the midst of the race to Berlin I wondered how he did it. Of course I hadn't seen Thurlow between the time I learned I was going and leaving; and in any case I never got on well with him. I would just have see for myself.

While we were in Italy Jiri (a Czech expat after all), told us what to expect behind the Iron Curtain. He talked mostly about East Germany. He told us everything was gray including people, cars, buildings, the sky, and dogs. All those things also looked the same everywhere you went, and nobody ever smiled even once. Arriving in Warsaw everything Jiri said was true but it was in Poland not East Germany (as yet). Add in horribly polluted air and water and the impression was complete.

We had four or five days in Warsaw before the first stage. We would go for a ride on open flat highways. One way in a block headwind, the other in a raging tailwind. Then we would go out and check out Warsaw in the rickety old free tram system. Back then the only spot in Warsaw one could call 'charming' was right downtown in what I think was called the 'university district'.

It was remarkable, then, that several years earlier Thurlow Rogers finished fourth overall. Details were scant in Velo News back then, and in the midst of the race to Berlin I wondered how he did it. Of course I hadn't seen Thurlow between the time I learned I was going and leaving; and in any case I never got on well with him. I would just have see for myself.

While we were in Italy Jiri (a Czech expat after all), told us what to expect behind the Iron Curtain. He talked mostly about East Germany. He told us everything was gray including people, cars, buildings, the sky, and dogs. All those things also looked the same everywhere you went, and nobody ever smiled even once. Arriving in Warsaw everything Jiri said was true but it was in Poland not East Germany (as yet). Add in horribly polluted air and water and the impression was complete.

We had four or five days in Warsaw before the first stage. We would go for a ride on open flat highways. One way in a block headwind, the other in a raging tailwind. Then we would go out and check out Warsaw in the rickety old free tram system. Back then the only spot in Warsaw one could call 'charming' was right downtown in what I think was called the 'university district'.

|

| What I wrote my parents at the time |

We were put in a hotel with several other of the teams. The elevator to the rooms was the slowest I have ever been in. It really was remarkably slow. But for the effort of doing the walking, taking the stairs would in fact been better. The food was horrible; overcooked pork or (presumably) cow meat. There would be a lump of usually mashed root vegetable and always a lump of clear gelatin with some carrot shavings inside. The sheer awfulness of what we were being served prompted us to search the streets for something with actual flavor. The only thing we could find (we being me, Chris Petty, and Chuck Veylupec), were street side sausage carts that had a bratwurst on a very good roll that you could buy for a pittance. Those really saved the day. We had been warned that in Poland there were only two things seriously worth buying there: leather and crystal. A few of the guys took advantage of cheap prices to score some leather jackets.

|

| My Peace Race Number |

|

| Peace Race Credential |

Our pre race time in Warsaw was uneventful other than Chris getting horribly sick as he had accidentally ingested some tap water. Fortunately he was better before the race started. We had been appointed a handler who told us how great things were in Poland, and drove a flashy Mercedes. Our rides out of Warsaw convinced us otherwise. Gray block apartment buildings went on forever, seemingly half of them unoccupied with the façade gone exposing the shoddy workmanship that made them uninhabitable in the first place. As Jiri told us East Germany would be, every person we saw was quite literally gray and never smiled. As it was May, gray clouds threatened rain that never fell. The sun came out a few times, but never for long.

|

| The very simple presentation of the stages in the race bible |

I remember that Tommy Matush managed 10th place in the sprint, and unfortunately, I think this would be our best result of the race. Furthermore, Tommy ended up dropping out a few stages later due to knee pain. The rest of the stages to Berlin would be long, boring, and amazingly uneventful as far as racing went.

|

| Lodz Keepsake - Front |

|

| Lodz Keepsake - Back |

Many of the towns we started or finished in gave everyone in the race a keepsake pennant or some other thing to give you to remember their city. Lodz was one I kept. Or it could be that some of the other cities gave less memorable things, like postcards.

|

Stages 3 and 4 were just more days of block headwind in flat open territory. As much as it made the going quite easy, I couldn't help feeling that we were being robbed of the true Peace Race experience. Even though I likely would have shelled out to the third or fourth echelons, but at least there would have been some action. Every day we rolled at about 20 mph, and with about 20km to go, the Eastern Bloc teams would form in front to create a huge combine to steamroll to the finish where Halupczok would fight it out with Olaf Ludwig, the Russian pretender to Abdoujaporov, or whoever the big Czechoslovak sprinter was (I can't seem to remember)…maybe Jan Svorada.

We also started learning to be smarter about getting to the dining halls. Where ever the hotel was, all the teams ate in the same place in a big room like a gymnasium or lecture hall within walking distance. Often it was across some big town square and people would wait outside with their kids to hound us for autographs. The first few days, ravenously hungry, we would charge outside as soon as dinner was open only to get besieged by children. We learned quickly to wait for the Polish team in Poland, and of course the East German team in East Germany. When we got tired of signing programs or whatever they shoved in our hands, we would say, "Look!, Uwe Ampler!", or "Olaf Ludwig!". They would look around and run off, not wanting to miss the real prize.

In the post- and pre-race talks Jiri was desperate for us to get some kind of result. I could understand the position he was in. This region was his former home and he had just recently gotten his head coach position with the U.S. national team. He had to prove his chops to the people back home. It wasn't enough that he had won the Milk Race in 1970. He had to prove he could coach a team of relative nobodies to miracles. In these flat stages with headwinds there really wasn't much we could do. Nothing was getting away with the East Block machine ready to run things down. Getting a result in a sprint was also pretty much out of the question since our sprinter had gone home, and we would likely get bruised and battered even trying to get into position for a sprint. It seemed to me it was better to wait for the mountains in Czechoslovakia. Chuck was a very good climber and I was climbing well, James was certainly in good form; why bang our heads against the wall trying to muscle our way into the combine? The only caveat to that was the possibility of cross winds. It looked like Stage 4 had the potential as we had two straight days of winds coming from the west, and Stage 4 was north-bound. However, we woke up to find the wind coming out of the north.

And so nothing happened until Stage 5 from Poznan, Poland to Cottbus in East Germany.

|

| Stage 5 - Into East Germany |

With about 20km to go, and now in East Germany, we were going over a cobbled stretch of road, slightly uphill and with a bit of a crosswind pressing us to the left hand side of the road. Jiri was standing on the right side of road shouting, "Get up to front and block!"

I let out a sigh, even as I was pressed in the left gutter. First off, I was, as a bike racer, morally opposed to the practice of blocking. Second, I already knew it was fruitless and possibly dangerous to attempt. But I had been ordered and so I felt obliged to try. The road turned and it was again a straight headwind. The chase had brought the break back to within reach, and they throttled back a little. I moved up to just behind the rotation and infiltrated the line. The East Block guys quickly saw what I was up to and what they did was just brilliant.

I was about a third of the way up the line and the guy in front of me called up to the guy coming back in the line to go through in his place. Since my wheel was overlapping his on the 'wrong' side, he simply rode me off to the right out of the rotation. Two guys more or less escorted me to the back of the chase and then got back in the echelon. That was my warning. I'm sure if I tried again, they would have hooked me to the ground.

A Bulgarian rider (I don't remember his name) attacked the break and stayed out for the win and the overall lead. The rest of the break including Steve got brought back. At the finish, it was a confused scene. Usually, staff would tell us where the hotel was, and we would just ride there as it was always pretty close by. This time however, we were being told to get on buses, bikes and all, to be driven to the hotel. I got to the disembarkation spot late as I didn't want to be in the scrum of guys competing to get on the first buses. The boarding was going fairly orderly for this bus, but I was still the last getting on. But then the driver of the bus put his hand up to the Dutch guy in front of me. The driver felt his bus was full, and closed the door on us. The bus drove off and the Dutch guy and I were left there, with no more buses in sight.

There was no one that looked like race staff around. I looked at the Dutch guy and asked "What the hell do we do now?" The Dutch guy responded by, without a word, getting on his bike and riding off in the direction the bus went (and it was already out of sight). I have no idea how long it took him to find the hotel, as I didn't follow. I was thinking to go back to the finish area to ask, when a tall, rail thin young teen girl asked me in carefully pronounced English if I needed to get to the hotel. "I know where it is,", she said, "Follow me." She started running as I rode along. "You don't have to run. I can slow down". "That's ok" she said, continuing to run. It took about 5-7 minutes to reach the hotel, and we arrived as the last guys were getting off the bus to which I had been refused entry. I wondered why we all didn't just ride there like usual. She wanted to talk more to practice her English and then wanted my address at home so she could write me. I obliged, giving her my parent's address in Wisconsin as I was otherwise essentially homeless when I left the country. I thanked her and gave her a water bottle (it was all I had). I asked her who her favorite rider was, she got a little sheepish smile and in a somewhat dreamy kind of voice said "Uwe Ampler"...of course. We would exchange letters for about two years. She would eventually send me a few chunks of what she said was the Berlin Wall. She sent a picture of herself and her sister standing on top of the rubble of the Wall.

It was also immediately apparent that East Germany, while no paradise, was considerably more cheery than Poland. Cottbus was clean and tidy. People smiled and talked to us. The food, again while not haute cuisine, was quite a few steps up from what we were being served in Poland. All this brightened my outlook considerably. Other than my blocking attempt in the past stage, I had done absolutely nothing in this race, except spend five to seven hours riding every day, as everyone had. I began thinking I should begin making some efforts to ramp up for the Czech portion of the race which was now not far off. I don't know if this was due to my brightened mood, or more that I was beginning to fell guilty about being able to do nothing about Jiri's increasing desperation for a result.

"Able" is the key word in the last sentence. So far it indeed had been useless to try and break into the lead out trains. The opportunity to try something, so far as our talents were concerned, just hadn't appeared. Nor was trying to force it seemingly worth the energy.

But you never know what's going to happen. Lead out trains can fizzle. A really fierce headwind could make the sprint more random. Of course we could finally get some cross winds. The finish of stage 6 from Cottbus to Halle would also mark the midway point of the race, with a rest day to follow.

|

| Stage 6 - Cottbus - Halle |

|

| The Halle keepsake - Front |

|

| The list of past winners in Halle |

It was another long flat stage with yet another block headwind. 211 km of easy pedaling made for a long boring day. The wind was so strong that as we approached the finish, the usual lead out trains weren't winding up. At last here was an opportunity. I started fighting for position about 20km to go. It was knuckle to knuckle contact the whole time, right on the wheel of the rider in front of you, the same behind. It was very tight and there was no choice but to wait for some movement ahead and being the first to react to move slightly enough to wedge yourself more to the front. It was this way the whole time, but a near crash to the left offered me a chance to move up a good chunk. I was now reasonably close to the front. I just had to concentrate and not lose position; stay vigilant and try to move up more. A small space opened to my front left, I began to slide into it when the Russian to my right and ahead of me made a radical move to jump into the same space. He raked my front wheel and I got taken down.

I was at the bottom of a pile of riders that spanned the whole road. From my spot on the ground I could have reached out and touched the 1km to go sign at the roadside. Indeed, we were not granted the same time as the bunch. It took quite a while to pick ourselves up and roll to the finish. I had road rash all down my left leg and it stung like crazy. I was in a lot of pain every time the wind blew on it.

Jiri had several bottles of second skin which was very painful upon application, but gave relief once dried. I was pretty beat up but otherwise ok. I hoped to use the rest day to regroup, and the two remaining East German stages into Berlin and Dresden to keep myself loose for the mountainous stages in Czechoslovakia. On the rest day we went out for a two hour roll 'round with the Dutch team. I talked with a guy who complained about having to race against "profies" while he had to work as a postal deliverer. "All these guys in Holland are getting money and do nothing but race...they are "profies" he told me. I did not tell him I was more or less the same as these "profies"...except I wasn't being given any money.

|

| Halle - Berlin |

Rinse and repeat. Another day with headwinds. Despite the changes in direction on the route, there was never enough of a side wind to create echelons. It was another long, slow slog across an uninteresting landscape. Getting close to Berlin, it again was the case that there weren't really strong lead out trains forming. The bunch was tense but I somehow managed to be in reasonably decent position. I was really thinking about having a go of it when finally the bunch got strung out and I was only 20 or 30 guys from the front. With a little luck, maybe I could get a decent placement with a momentum swing.

Luck, however, was definitely not on my side. Within the final kilometer, in the third to last corner (see finish detail above) the Cuban rider in front of me started drifting on the brick street surface and panicking a bit locked up his rear wheel briefly. In a combination of his radically slowing down when we were moving very quickly, my overlapping his rear wheel at precisely the wrong time, my front wheel got clipped by his rear wheel, and I high sided, falling over to the left.

I blacked out for not an entirely insignificant time because the next thing I remembered was looking down the road and seeing the back of the caravan speeding around the next corner. I sprang up and in beginning to swing my leg over the bike was hit by blinding pain. Looking straight ahead with my left arm on the bars, my right on the saddle, and gasping in pain, everything in my right field of vision went black; with a sharply defining line, I had clear vision to the left. I regained full vision in a few seconds. I partially collapsed on the top tube of my bike and I heard Jiri, "Vas ist de masser? Get back on the bike!" I felt someone feeling around my shoulders, "No," I heard a heavy German accent say, "It is fractured."

I was turned around and led to an ambulance. I was flooded with a great feeling of loss and started sobbing, but had to stop because that hurt too much. Loss is the best word I can think of to describe how I felt when forces beyond my control prevented me from racing. Often, when I was expecting to get into a big race, but then the opportunity was taken away, or at the end of a race circumstances might be that I was prevented from being able to race it out; the feeling of loss came out as a frustration that always took too long to evaporate. This time it was deep sorrow. Not for all the work I had done to get here, that was a sunk cost. The loss I felt was the loss of opportunity. Gone was any chance to actually race in a few day's time. And long gone now was any chance at the Worlds road team. I was a long shot in any case, but now there was no chance at all. I had been thinking that if I wasn't able to get a result here, I would at least be nicely set up for nationals. They were in Park City on a punchy course that favored me. I would heal in time for it, but my form would be gone. All these things and more were wiped away now, taken from me. Laying on the gurney in the ambulance I could only breathe heavily in place of shedding tears while my left shoulder throbbed with pain.

Curiously, we drove around stopping at 4 hospitals (at each there was a lot of talking and arguing in German) before they finally wheeled me out of the ambulance, transferred me to a another gurney and into a hospital. It seemed odd. It was a big cavernous room with a high ceiling. They laid a heavy lead cover over me and took an x-ray. A head moved into my field of vision and said: "Ve are going to haff to oberate". "Ok," I replied with a little bit of nervousness in my voice. I saw them pass the biggest needle I had ever seen over me; and shortly after that felt it pinch and slide into my upper inside left thigh. I gasped and tensed up, which made my shoulder hurt again.

They wheeled me down a corridor as I faded into unconsciousness.

***********

I was shaken awake by an orderly holding a bedpan. He made a motion as if he were pissing into it and looked to me for acknowledgement. I nodded that I understood. It was dark in the room but I could tell I had a roommate, and that my left arm was immobilized wrapped up mummy style to my torso. I went back to sleep.

Jiri came to see me in the morning and dropped off my bag. He had some conciliatory words for me and said he would arrange a flight for me to meet them in Amsterdam to fly back to Chicago. That meant a full six days I would be at the hospital in East Berlin. I had never spent more than an hour in a hospital before let alone one in a foreign country; let additionally alone in a country with a drastically different political and economic structure.

After Jiri left a nurse came in with a hospital gown. I was more than ready to get out of the torn bloody shorts that I had been in for nearly 24 hours. I carefully got myself off the bed and with some difficulty I wriggled the shorts off. I reached out for the gown but the nurse instead of handing me the gown was staring directly at my penis. I knew that in Germany nudity in general is no big deal, which was why indeed I found the staring quite unprofessional. It was just then that it occurred to me that she had probably never seen a circumcised one before. Finally she snapped out of it and handed me the gown.

Later in the day a man from the East German cycling association and a woman from the swimming association (along because she spoke English) came by and lent me a small black and white television and a Walkman with 4 tapes: The Beatles White Album, a collection of Rolling Stones hits, and two Euro Pop albums I neither recognized or could bear listening to. The TV wasn't terribly handy as all that was on were usually visually uninteresting programs in German . I could watch the Peace Race going on without me in the late afternoon though.

|

| It's still in me. |

|

| State Dept. Letter to alert my Parents...apparently it didn't reach them before I'd arrived back in Albuquerque. |

After a few days it occurred to me that once the doctor checked on me in the morning I could go out of the hospital and have a look around, as long as I was back for the doctor to check on me in the late afternoon. I found that there was a nice very large park a short distance away. There were beer stands all over the park and for the equivalent of about five cents you could buy a beer, walk about the park and return the mug at any other of the beer stands. There was a cherry beer that was quite good that quickly became my favorite. I would sit on a park bench and people watch.

My hospital roommate was a heavyset middle aged man who apparently had been in an agricultural or industrial accident that left very distinctive uniform perforations on his shin. His family came in to visit him every day and while they spoke no English, and my German was very limited, they often tried to communicate with me and express their pity for me. They also sometimes brought me some fruit, which was very much appreciated.

On my second to last day at the hospital, the man from the cycling association and the woman from the swimming association came by in the morning and told me they were going to show me around Berlin. They of course didn't show me the wall between East and West Berlin, but they did take me up a tower that gave a commanding view of the entire area including the famous wall. They also took me to a very nice sporting center with weight rooms, ball courts, and a swimming pool half in and half outdoors. Outside also was nice 400 meter running track, tennis courts and the like. We stopped for a lunch of sausages and tea. The day concluded with a visit to the zoo. The only thing I remember from that visit was a sad looking road runner bird in a small cage. Given that the road runner is the state bird of New Mexico, I was quite aware of the bird's poor state, although also given the bird's limited world range, I was quite impressed they even had one.

Two mornings later they were back at the hospital to take me to the airport. They collected the TV and the Walkman and tapes. I thanked them for their hospitality and flew to Amsterdam. I met my teammates at the gate for Chicago. Chuck bought me Hagen Daz bar and I asked him how the rest of the race went. He was evasive about any detail about racing and went straight for the after race party in Prague. That told me that basically little had changed about the nature of the race. Would it had been any different for me? I couldn't know.

The stages I missed:

From Chicago I flew back to Albuquerque. Drew Gagne picked me up the airport and a week later took me to a doctor to unwrap the bandages and get the stitches over my collarbone out. The doctor took some x-rays and said I would never break that side again. My Shaklee team issue Cyclops with Dura Ace was waiting for me when I got back so I put it together and resumed riding immediately. It would be another month before I would start racing though. Rather than continue sponging off my friends in Albuquerque, I arranged to go back home to the farm in Wisconsin. My younger brother Stephen drove to my uncle Don's house in Salida Colorado, and I hitchhiked, with my bike, up to Salida. My friend Waz drove me up just past Santa Fe, and I promptly was picked up by a fast driving Chicano from Espanola that fortunately for me was headed even farther north to Ojo Caliente. From there, I got a ride from a hippie type in a Volvo that was headed for Breckenridge...perfect, he could deliver me right to Salida.

After few days in the beautifully peaceful town of Salida, Stephen and I drove back to Wisconsin, with a few landmark stops, including the Devil's Tower in Wyoming, the Black Hills and Badlands of South Dakota. Back at the farm, I trained on my beautiful, familiar old roads and helped a little at the farm. The local newspaper came out to check up on me and got this shot of me headed out for a ride.

|

| Front page stuff! Pierce County Herald June 21st 1989 - Me with my new Cyclops back in Wisconsin. |

I returned to racing in Northern Iowa in late June and was surprised that I hadn't lost quite as much sharpness as I had thought. I carried some form to Superweek in Milwaukee where I managed fourth at the Lakefront, where I had won in '86. Next stop was the National Road Championships in Park City Utah. I skipped the Time Trials. I started the Road Race with little expectation but got to the front in time for the first big hill on the course and drilled it. This touched off a high-speed battle that really stretched the field. I was safely ensconced in what was left of the bunch when I broke a spoke on the last lap. I limped it in for nearly last place with Ranjeet Grewal. Ranjeet's brother Rishi was the winner.

Following nationals I returned to Albuquerque and had a fun and relaxed late summer and fall of racing and collecting some prize money. I picked up a nice win at the Morgul Bismarck stage race in Boulder. It was just two stages, a road race and a crit, and based on points rather than time. On the famed Morgul Bismarck road circuit, I got away early with James Urbonas. We were hammering all out but the bunch was closing in as we approached the Hump for the last time. James had done a big turn before the Hump and couldn't follow me when I did my turn on the hill. I kept the pressure on all the way to and up the Wall, and just held off Marty Jemison for the win. Rod Bush guided me through the bunch in the crit at the Celestial Seasonings warehouse so I could sprint to fourth and score the GC win as well.

John Frey, Rod Bush, and I did an east coast swing where we flew to Nashville, rented a car and drove to races in Greensboro, NC; Albany, NY, and finally the A to Z Road Race from Athens to Zanesville in Ohio. We also hit the Retailer Classic in Oklahoma City, and various races in Texas. My living arrangements improved vastly as, thanks to Paul Sery, I had a room in a centrally located house with a very flexible and inexpensive rent payment requirement.

Jiri hadn't written me off either. At nationals he told me he liked what he saw from me in Italy and had plans for me the next year. First he wanted to get me back in top form, and promised me trips to the Vuelta a Guatemala in late October (post here) and then the Vuelta a Costa Rica in December (post here). Things began looking up for me heading into late fall. Frank Scioscia (the Shaklee team director) also promised me cash for the next season. With prize money earned in the late summer and fall, I had enough money (barely) to pay rent and feed myself. There was nothing left over for things like beer or entertainment. After returning from Costa Rica, I spent the winter riding and sitting on the couch, and came in 1990 feeling very ready to race.